Chapter outline and page reference:

Shell Inscriptions at Junagadh 252

Uparkot ‘Buddhist’ Caves 254

Khapra Khodia Caves 264

Baba Pyara Caves 269

Mai Gadechi Cave 281

Sakario Timbo 285

Pancheshwar Caves 286

Naudurga 287

Ghoda Khan 287

Cave Complex Adjacent Do Pir Dargah 288

Further Junagadh Caves 288

Chapter preview (first three pages only):

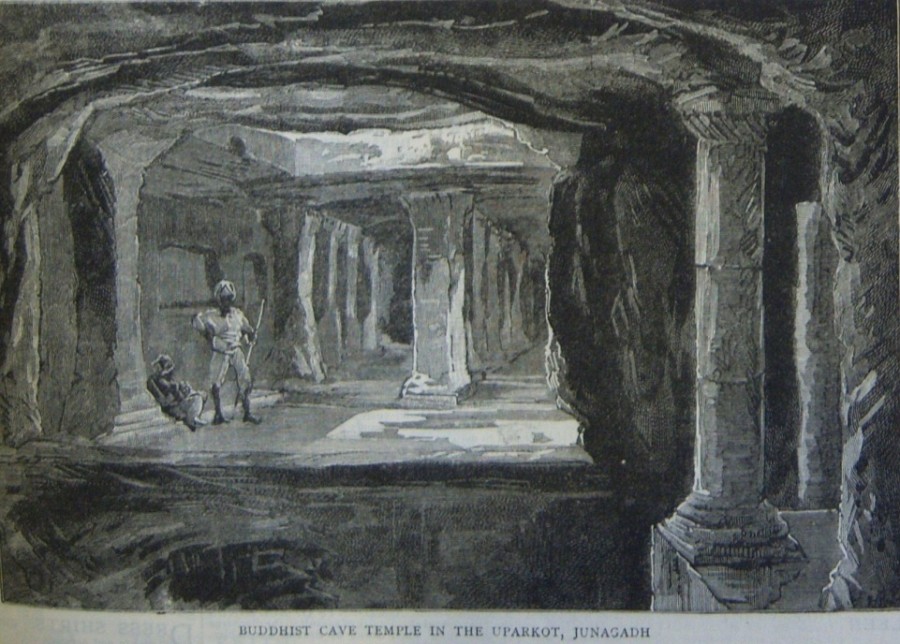

Figure 52. ‘Buddhist cave temple in the Uparkot, Junagadh’, a sketch by Surgeon-Major Lewis A Irving (from The Graphic 1887).

There are several rock-cut cave complexes in Junagadh, three of which are situated on or around the fortified area of Uparkot. According to Burgess (1875, 1876), there must have been many more before the commencement of destructive quarrying in the area. The earliest surviving examples, datable to about 2nd century AD, are the Baba Pyara complex, situated at the southern foot of the fort, and the Khapra Khodia complex near its northern base. The Uparkot Caves located within the fort area itself, are somewhat later according to Meister et al (1988), datable to about 400 AD, although Soundara Rajan (1985) suggested that they date from the 2nd century AD. Interestingly, they are cut into the rock from above, rather than from the side like the rock-cut complexes in the Deccan. Pradhan (1930) suspected that these rock-cut apartments date from what he described as ‘pre-Aryan’ times, and that ‘they were used by the Buddhist monks and ascetics in later times’. According to Kail (1975, page 53): ‘The monasteries at Junagadh were the productions of the early Buddhists who reached the Kathiawar peninsula in the third century B.C., if not earlier. They subsequently passed to the Jains and finally reverted to the followers of the Great Vehicle. Hsuan Tsang, the Chinese traveller, when he visited this area in the seventh century, found many monasteries and convents of the Mahayana Buddhists.’

Figure 53. Map of Junagadh showing important archaeological monuments (from Soundara Rajan 1985).

Shell Inscriptions at Junagadh

Salomon (1977–78) located in Junagadh a total of 80 shell inscriptions, 53 at Khapra Khodia Caves, 23 at Mai Gadechi Cave, and 4 at Baba Pyara Caves. Shell inscriptions are written in Sankhalipi or ‘shell characters’, and like Ornate Brahmi, it is a highly ornate script, also evidently used for signatures, and was in wide use over virtually all of India except the far south, from approximately the 4th to the 8th centuries AD. Over 600 examples of this script are now known. The characters are highly stylized, tending to conform to a general shape superficially resembling a conch shell or sankha, whence the name applied to the script. Statistical and formal analysis of the characters indicates that they are derived from the characters of standard Brahmi, but the changes are so extensive that it is still very difficult to authoritatively identify them. Several claims of decipherment have been put forward, but they are not convincing (Salomon 1998).

Distributed around the pillars, pilasters, and inner walls of the Mai Gadechi Cave are 23 inscriptions in shell characters. Many of them are worn or otherwise damaged; some have been repeatedly painted over, while others are obscured by heaps of refuse within the cave. One of the better preserved specimens is on the side of the pilaster at the front of the cave on the right side. There are no inscriptions in Brahmi or other ‘normal’ scripts in the cave (Salomon 1977–78).

Two inscriptions at the Baba Pyara Caves are written vertically on the back of the front wall of cave no. 12, on the right side. Another runs down the side of the left-hand door leading into the rear chamber of the same cave. Traces of a fourth inscription are visible on the left side of the gateway leading to caves 13–16. The Bawa Pyara inscriptions were unknown before Salomon (1977–78).

Salomon (1977–78) reported of the Khapra Khodia Caves that: ‘the entire complex is a virtually unexplored mine of ancient inscriptions in shell and other characters. The inscriptions in the caves have been numbered in white paint, with the total running to 175. These include, besides shell inscriptions, graffiti in various forms of Brahmi, simple and ornamental, and Urdu and other modern scripts, as well as many more or less unrecognizable fragments. The shell inscriptions number at least 53: due to the rough condition of the caves and the poor light in many of them, several inscriptions could not be definitely identified. An intensive survey of this important but little known site would probably reveal still more shell inscriptions. The shell inscriptions appear on various pillars and walls throughout the cave complex. A few are inscribed on the upper parts of the walls of the sub-caves… The different inscriptions embrace a wide variety of styles, from the ornate and calligraphic, down to extremely crude graffiti. Some are accompanied by decorative elements such as the figure of a horse. On the whole the inscriptions at this site (as is regrettably so often the case) are in poor condition… Although the numbering of the inscriptions indicates that at some time a survey was made, these inscriptions have apparently not been previously reported in any published work. These caves are of considerable historic, epigraphic, and architectural interest, and merit a more comprehensive study than I was able to undertake in the brief time available to me.’