Deloche (1993, page 103) noted that: ‘The access to temples set in the heights is frequently made easier by means of gigantic stairways… on the Kathiyavad peninsula even more spectacular stairways ascend to the extraordinary mountains sacred to the Jains, the Satrumjaya at Palitana, and the Girinagara or Girnar mountains at Junagadh. These ‘megalithic’ works are, however, only to be found at certain places of pilgrimage, or in a few fortified towns. Elsewhere, there is no trace.’ Referring to Mount Girnar, Stevenson (1910, page 85) noted that: ‘…its summit is gained by the most magnificent stairway in the world, flight upon flight of stone steps which lead from the plain beneath, past the Neminatha fortress with its wealth of temples, to the highest of the five peaks, some 3,666 feet above the level of the sea.’

The main stairway at Girnar starts at about 168 m above sea level and climbs to Gorakhnath Peak (1117 m), the highest point in Gujarat, before descending to Kamandal Kund (about 954 m) and again ascending to, and ending at, Dattatrey Peak (1066 m). Two major attractions on route are the cluster of Jain temples at Dev-kot (930 m) and the Ambaji Temple (1021 m). Eck (1998) wrote that: ‘the pilgrim track up the peaks is so well established that it has long since been made into a giant, steep, winding stone staircase, some 10,000 steps in length.’ Edwardes and Fraser (1907) called these stairs: ‘…the greatest staircase in the world.’ Forbes-Lindsay (1903) described the stairway climb to the Jain temples at Dev-kot: ‘The ascent to the temples is by no means easy. It may, however, be made in a duli. For about two-thirds of the distance the way is somewhat roughly paved. There is a rest-house at each five hundred feet elevation, until a height of fifteen hundred feet above the plain has been reached. The next thousand feet is along a path which skirts the edge of the precipice, and is so narrow that the duli bearers have hardly room to proceed. The scarped rock rises in a sheer wall two hundred or more feet above the foot-way. At the top of this wall, or cliff, on an extensive level, about six hundred feet from the summit of the mountain, stand sixteen temples.’

Figure 29. Photograph of Gorakhnath and Dattatrey Peaks from the Temple of Ambaji, taken by F. Nelson in 1895 from the Lee-Warner Collection: ‘Photographs of Junagadh’. The photograph shows the rough stone steps, climbing the western side of Gorakhnath, before the new stairway was built (from British Library Online Gallery).

Although KLS (1931) referred to the Girnar stairway as ‘surely the longest stairway known, and one which must strike awe even into the hearts of modern flat dwellers’, the title belongs, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, to Spiez’s Niesenbahn funicular railway. The service stairway for this Swiss attraction has 11,674 steps going up 5,476 feet, or slightly more than a mile. It is 3,499 m long and was constructed in 1906–1910. Nevertheless, the Girnar stairway is one of the greatest stairways in the world, and is doubtless the longest completely stone stairway.

Hemvallabhvijay (2013b) has given a detailed description of the important installations adjacent the stairway, along the route from the foot of Mount Girnar up to the Jain temples at Devkot: ‘…as one enters through the main gate of the great mountains of Girnar, the temple of Chadav Hanuman can be seen on the left. To the right, next to the police station is a temple with the east facing footprints of Lord Neminath. Lakshmichand Pragji, who belonged to the Vishashrimali sect, built this temple. An idol of the guarding and presiding goddess of Girnar, Ambikadevi has been placed in a wall below the footprints.

‘In the Vikram Samvat year 1212 (1156 A.C.) Ambad, a Jain householder, commissioned the construction of suitable steps thus making the ascent easier and more convenient. Thereafter, several references have been found documenting the restoration of these steps from time to time.

‘About 15 steps ahead of this temple, is the place where the litter bearers gather and about 85 steps further ahead is the temple of the five Pandavs i.e. five small temples, four of which are on the left and one is on the right. Currently, only the old foundations and ruins of these temples are visible. At the 200th step mark, there is the Chunaderi or Tapsi water house. Further ahead at the 500th step, one finds the Chodiya water house to the right, where recently a new resting place has been built. Up ahead on the left is a Rayan tree, where one finds a water house as well. At the 800th step is the site of goddess Khodiyar. Further up near the 1150th step, is a small temple of Jatashankar Mahadev. At the 1200th step, on the left, a new resting place has been constructed. Moving further upto the 1500th step, there is a place known as Dholideri and even here a new resting place has been built. Proceeding uphill on the 1950th step, you reach the Kalideri where you find a resting place as well. Here, relics of an old building bearing a name plaque, Dhaniparab are seen . At the 2000th step, there is a small track on the left that leads to the memorial monument of Velnath bapu. Who are courageous and adventurous enough, can go to Sahsavan via this shorter mountain route. Approximately at the 2200th step, is the cave of Bharthari, and at the 2300th step are the Maali water house and the Ramji temple. Carved on a stone to the left of this water house is an inscription that reads,…

‘(in the year of V.S. 1222)

‘(1166 A.C.) member of the Shreemal sect, son of Rani, Ambad made these steps). Nearby is a reservoir filled with sweet and cool water. A separate inscription there notes that this reservoir was built on the advice of Shri Prabhanandsuri Maharaj sahib in the Vikram Samvat year 1244 (1188 A.C.).

‘After a somewhat steep climb and reaching the 2450th step, one can visualize the ‘Kausaggiya rock’ and the ancient ‘Haathi (elephant) pashan (stone). Currently however, fearing the slippery slope of the mountain here, the administrative officials have covered the place with cement and concrete, thus completely obstructing the pashan. Further up near the 2600th step is the rock of Ranakdevi and a wall inscription near the 2650th step, which reads, (On Monday, the 6th day of the second half of the Kartik month in the year 1683 (1627 A.C.) Singhji Meghji, of the Shrimaal sect and representing the Deev community, got the east boundary of Girnar renovated).

‘After a steep climb on the right at about the 2850th step, lies a small temple with a meshed iron grill and even today statues of Jain Lords can be seen engraved inside this temple. Further ahead is the Dholokund or the white reservoir located near about 2900th step. Up ahead at approximately 3100th step, Goddess Khodiyar is located in the hollow of a wall on the left. At the step number 3200 is a place called Khabutri or ‘Kabutri Khan’ where many hollows can be seen in a black rock. At about the 3400th step, past the water house is a small shrine of the “Suvavdi Mata” where women pray for obtainment of a child. The place around the 3550th step is known as the Pancheshwar place and currently small temples of Santoshimaa, Bharatmata, Khodiyarmaa, Varudimaa’s, Goddess Mahakali and Kalika maa’s are located here. Moving up ahead after the 3800th step, one come to the gate of the Uparkot fort, also known as Devkot. Narshi Keshavji got a floor constructed above this gate, which currently houses the offices of the Forest Protection Division.’

Before the 12th century there were no steps up the west face of Girnar. Early work on the flight of stairs up the west face was accomplished by Ambaka (the Jain minister or dandanayaka Amradev), the son of Udayana, the minister of King Kumarapala (1144–1172 AD). Mortally wounded in battle, the dying minister requested his sons, Bahada and Ambada, to carry out his plan of constructing, inter alia, a flight of stairs at Girnar; the dutiful sons duly executed the work (in 1164 AD), as an inscription shows (Altekar 1924–5, Dhaky 1980, Shree Jain Prarthana Mandir Trust 2002). According to Shastri (1989): ‘It was during the reign of King Kumarapala who led his sangha from Mt. Satrunjaya to Mt. Girnar but himself could not ascend the hill, as there was no stairway. At his instance Ambaka provided for the padyas (stairways) in V.S. 1222–23’ (see Jinavijaya 1921, nos. 50–51). An inscription from Girnar, translated by Hari Waman Limaya, probably records this construction work (Limaya 1876): ‘In the year Samvat 1222 [1165 AD] a foot-path was constructed by the powerful and prosperous Vaka, the son of the respected Raniga of the family of the prosperous Malas.’ Two other inscriptions records the same thing (Limaya 1876): ‘In the year Samvat 1222 a foot-path was constructed by the prosperous and powerful Avaka, the son of the respected Raniga of the family of the illustrious Malas’ and ‘In the year 1223 of Vikrama a paved foot-path was made by Avaka, the son of the respected Miraniga.’ The Revantagirirasu by Vijay-Sen-Suri gives the date VS 1220 (1164 AD) for this work. The Kumarapalapratibodha informs us that, at the suggestion of Siddhapala, the son of Sripala, Kumarapala appointed Raniga’s son Amra as the governor of Saurashtra and entrusted the work of building steps for Girnar to him (Chatterjee 1984, page 73, note 163). According to the Kumarapalaprabandha (1435 AD), the steps were built at a cost of a lakh of drammas (Indraji and Jackson 1896). Dhaky (1980, note 51, page 30) pointed out that: ‘The Revantagirirasu (c. A.D. 1232) gives the date V.S. 1220/A.D. 1164 for this work. Ambaka’s own short inscriptions to the effect give the dates V.S. 1222 and V.S. 1223 (A.D. 1166 and 1167). The date 1164 A.D. may refer to the beginning and 1167 to the end of the work.’ Also see Acharya (1942, nos. 152 and 153) for these inscriptions (Shastri 1989, page 161).

According to Ratna-Prabha Vijaya (1948–50, part II, page 71), King Kumarapala’s minister, Udayana, made a vow to have constructed railings on the sides of the pathway leading up to the top of Mount Girnar. After the death of Udayana, his son Bahada went to Girnar to construct the masonry hedge on the sides of the path, but being at a loss as to what to do and from where the masonry hedge should begin, he started the penance of ‘attham’ and adored the goddess Ambika. The goddess presented herself and said ‘where I scatter rice-corn, the said work should be constructed’. Then 63 lacs (6,300,000) of rupees were spent and the work was completed.

‘According to the Prabandhacintamani [(1304 AD)], an earthquake occurred when the king [Kumarapala] was at Girnar on his way to Somanatha. The old ascent of Girnar was from the north called Chhatrasila that is the umbrella or overhanging rocks. Hemacharya said if two persons went up together the Chhatrasila rocks would fall and crush them. So the king ordered Amrabhatta to build steps on the west or Junagadh face at a cost of 63 lakhs of drammas’ (Indraji and Jackson 1896).

Diskalkar (1938) noted that: ‘The building of steps on the holy Girnar hill is attributed by Prabhavakacharita and Prabandhachintamani to Vagada or Vagbhata. But we know from two inscriptions on Girnar of V.S. 1222 and 1223 (Cousen’s list of Antiquarian remains in Bom. Pres. P. 359) that the builder of steps was Ambaka who was the son of Raniga’.

In 1627 AD the stairway was restored by an association of pilgrims (Menant 1907). An inscription from Girnar, translated by Hari Waman Limaya, probably records this repair work (Limaya 1876): ‘In the auspicious and prosperous year Samvat 1681 [1625 AD], in the month of Kartika, dark fortnight, 6th day, Monday, the repairing work of the steps to the eastern part of the holy and prosperous place, Girnar, was begun by Singhaji Meghaji of the family of Mala [4th line unintelligible]’. For the original inscription see Burgess (1875). Burgess and Cousens (1897) indicated that this inscription is near Hathi-pagla, and he gave another translation: ‘Monday, the 6th of Kartika Vadi, Samvat 1683; the repair of the road on this sacred place of Girnar has been made by the exertion of the meritorious Mansimhaji Meghaji of the Srimali caste in a pilgrim-party from Diva [Diu].’ The inscription can be found on the wall of Bhim Kund (Shukla 1932).

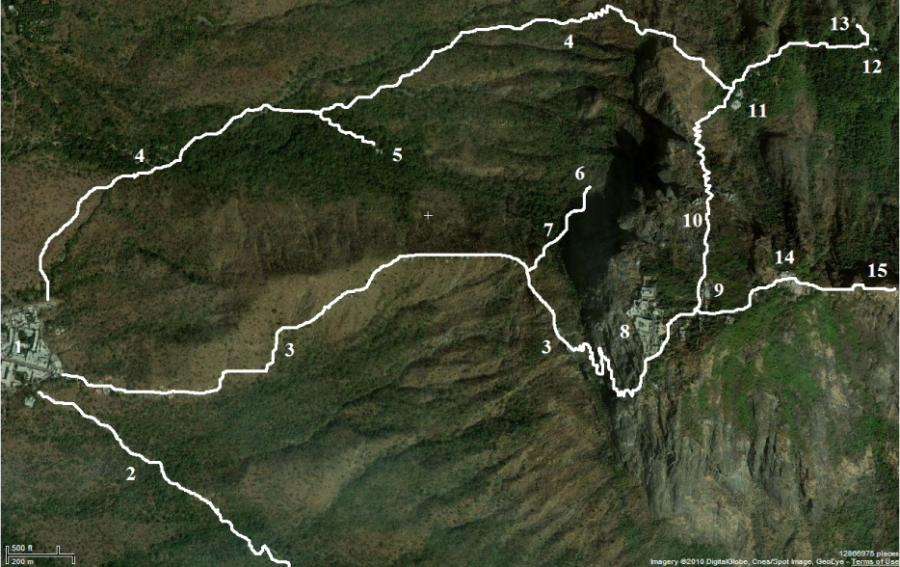

Figure 30. Vertical aerial view of some sites and paths east of Bhavnath Taleti, Mount Girnar. 1 – eastern edge of Bhavnath Taleti; 2 – motorable unsealed road to Bordevi Temple; 3 – main stairway to the top of Girnar; 4 – alternative stairway; 5 – Jatashankar Temple; 6 – Vagnath Temple; 7 – minor path to Vagnath Temple; 8 – Dev-kot; 9 – Gaumukhi Ganga; 10 – Sevadas Ashram; 11 – Seshavan Jain Temple; 12 – Sitamadhi Temple; 13 – Hanumandhara Temple; 14 – Ambaji Temple; 15 – Gorakhnath Temple (from WikiMapia 2010).

There are records that show that local Svetambar Jains ‘used to carry out the repairs to the steps at all places on the Hill, namely from the base to the 5th peak and from the Gaumukh to Sheshavan and Hanumandhara’ from 1774 to 1893 AD. The steps from Gaumukh to Sheshavan were reconstructed in 1828 AD, and those from Dev-kot to Dattatrey Peak were renovated in 1844 and 1864 AD. In 1870 a further 7,002 koris were spent on repair of the stairs after a detailed inspection was carried out by Jemadar Mubarak (Shukla 1932).

Referring to the ascent at Girnar in 1873, Booth (1912, page 126) noted that: ‘…three-fourths of the approach from Junaghud to the first summit, some five miles, was a rude pathway either paved with rough granite boulders or made on the natural surface anyhow, without regard to gradients; and a very precipitous and hard three to four hours’ climb it was.’

The Junagadh Darbar made some repairs to the stairs in 1887 AD on the occasion of the visit of the Governor of Bombay (Shukla 1932).

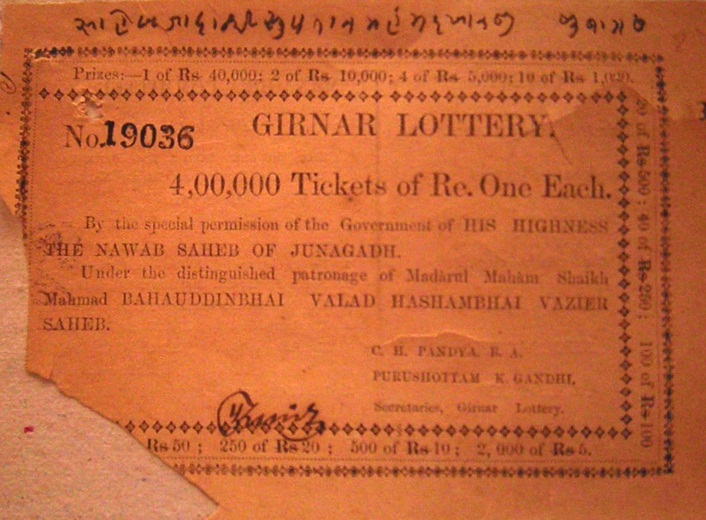

During the time of Mohammad Bahadur Khanji III, in 1889 AD renewed construction of stone steps was begun in order to facilitate ascent upon the Girnar, by collecting money by means of a lottery (JunaGadh State 2007). Haridas Viharidas Desai, Diwan of Junagadh, raised 300,000 rupees from the 1888 public lottery to build the 12,000 stone steps. It took almost 20 years before the steps could be completed in 1908 during the rule of Sir Rasul Khanji Babi Bahadur, the Nawab of Junagadh. The money was raised initially by Haridas and the work continued by Bechardas, who became Diwan of Junagadh in 1895 after his brother’s death. The lottery was supervised by the chief medical officer to Junagadh State, Dr Tribhuvandas Motichand Shah (Rupera 2008). The stone steps leading to the top of the Girnar and Datar Hills are all made from locally quarried white limestone. It was reported in 1903 (Junagadh State 1903b) that the principal quarries at Junagadh were known as Kabutri Khan, and that to provide facilities for the exportation of these stones a railway line 2½ miles (4 km) long was constructed from the Junagadh station at a cost of Rs 54,480.

Figure 31. One of the original 400,000 lottery tickets, sold at one rupee each with the object of raising funds to build and repair the Girnar stairs, in the collection of Mr P Rupani (photo by Wainer 2010).

A committee set up to raise funds for repairs to the stairway in 1968 managed to collect Rs 10,000 which was handed over to the Government, but Anonymous (1975) suggested that no improvement occurred. When part of the stairway wall collapsed in 1975 twenty-seven people fell to their deaths. The incident occurred during a rush of pilgrims when 200,000 people attended the event of a full or ‘sampoorna’ Shivaratri, the first in 36 years (Anonymous 1975). The location of this accident was near the Ranakdevi site (Ranakdevi’s Stone), between Mali Parab and the above Jain temple site of Dev-kot. To compensate relatives of the dead, the State Government sanctioned the grand sum of Rs 500 to the family of every male earning member deceased, and Rs. 250 in every other case, subject to a maximum of Rs 1,500 per family (Lok Sabha 1975).

As a result of heavy rains in August 2007 some of the steps near Gaumukhi Ganga Temple were washed away, resulting in a deep drop of 15 m into the valley, and preventing access to Ambaji Temple.

It is said that the road which takes you to the beginning of the climb actually takes you to step number 3000, as this is how far it is from Damodar Kund, leaving only 7000 to the top (Sajnani 2001, Beattie and Chowdhury 1996). From the base of the stairway to the Amba Temple, at about 5,000 steps, every 100th step is painted with its number. The number of steps to Mali Parab is about 2,200, to the Jain temples at Dev-kot about 4,000, to Gorakhnath Peak about 6,000, to Kamandal Kund about 7,000 and to Dattatrey Peak about 8,000 (although it is claimed that there are exactly 9,999 steps from the trailhead to this last temple). Amarji (1882, page 29) has informed us that: ‘From the gate of the fort [of Dev-kot] up to the mandap of Sri Girnar Mata [= Amba Temple] there are 1096 stone steps, and from Gaumukh to Hanumandvara there are 968.’

Figure 32. Photograph of Gorakhnath and Dattatrey Peaks from the Temple of Ambaji, taken by a photographer of the Solankee Studio around 1900. The new stairway climbing the western side of Gorakhnath is clearly visible (from British Library Online Gallery).

There is another stone stairway to the top of Girnar, today much less used than the main stairway, which Ward (1994) suggested was hewn out in the 1980s. This in fact is the original route to ascend Girnar, before the 12th century construction of the stairs on the west face, as is seen in the Satrunjaya Mahatmya (Shukla 1932). The stairway can be reached by walking about 200 m north of the base of the main stairway, or about 100 m east of Sudashan Talav which is behind the Bhavnath Temple. The stairway passes a side path on the right to nearby Jatashankar Temple (320 m) after about 1 km. After a further 1 km the stairway reaches the north-west spur (Koribara Ridge) at 570 m and then climbs this spur another 500 m to reach Seshavan (732 m). From Girnar Taleti to Seshavan there are about 2,800 steps on the stone stairway. From Seshavan one can continue climbing south for about 800 m, first climbing about 1,200 steps before descending a further 200 steps, to reach the Jain Temples at Dev-kot and the main stairway, or descend to the north-east past Bharatvan to reach Hanumandhara (610 m) after about 500 m. This north-west stairway provides quicker access to Seshavan and Hanumandhara than the main western stairway.

Figure 33. Dolis and weighing scales near the beginning of the main stairway up Girnar (photo by Wainer 2008).

Eastwick (1881) reported about 130 years ago, that to ascend Girnar by doli, in those days carried by four men rather than two as at the present time, would cost 4 or 5 rupees. This comment was repeated by others, such as Khandekar (1894, page 375) and Murray (1898, page 158), who noted that: ‘Unless the visitor be a very good climber, he will do well to get into a doli, which can be had for 3 or 4 rupees according to tariff.’

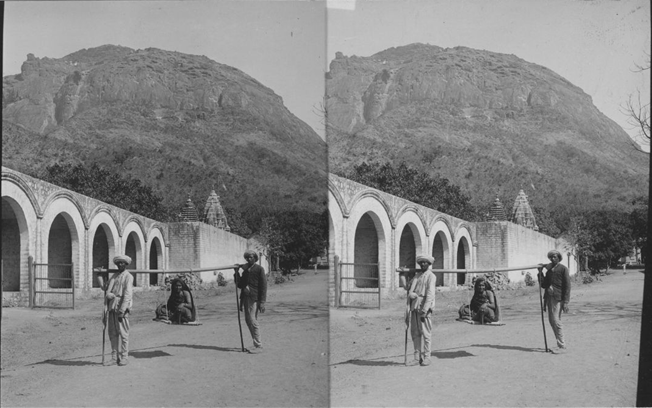

Figure . Stereoscopic image of Girnar, showing doli and doli men (Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside) (from Online Archive of California 2009).

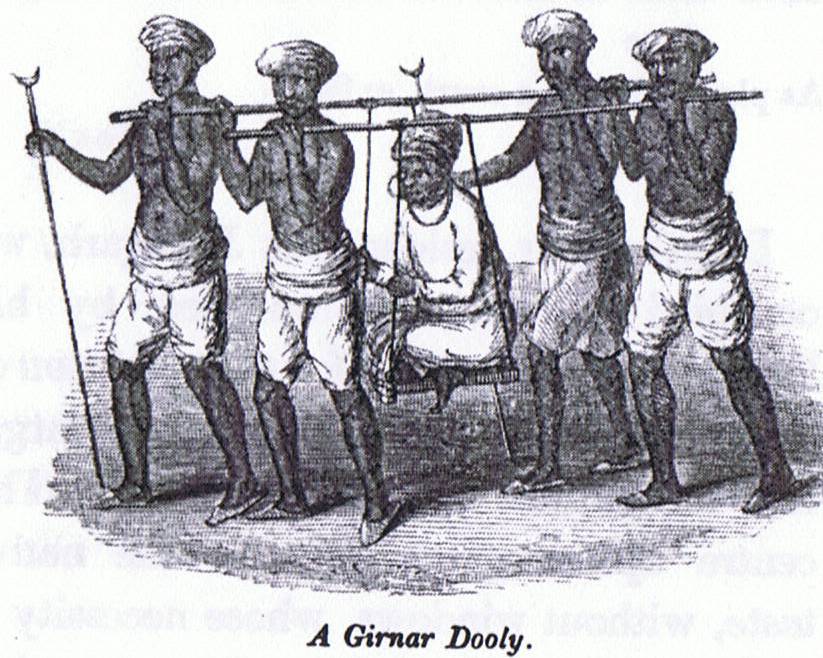

About 100 years ago, Mellor (1914) wrote that: ‘The usual plan is to be carried in a “dholi,” which is a seat, or tray, about 18 inches square, slung from two poles, and carried by four men. The path frequently passes along the edge of the precipice, and is so narrow that the dholi almost grazes the scarp, which in some places rises hundreds of feet above the path.’ Booth (1912, page 130) also described these dolis: ‘The dhooly is simply an ordinary chair with arms, to which are fastened a couple of stout poles in front and two behind, and the passenger sits on the chair. The dhooly wallahs each carry a long stick shod with iron in one hand, while the other is thrown over the pole which rests on his shoulder. The stick helps to support and balance them over rough or eneven ground.’

A note suggesting the difficult financial circumstances of doliwalas was provided by Anonymous (1946): ‘The Government of His Highness the Nawab Saheb Bahadur, Junagadh have sanctioned an increase of 33⅓% in the Doli charges for visits to the sacred Girnar and Datar Hills as a permanent measure of relief to the Doliwalas, due to the general rise in prices, and have cancelled the concession rates for State guests and State servants on duty. The relief has been greatly appreciated by the Doliwalas.’ Nowadays, for those who weigh up to 50 kg, for the journey to Dev-kot it costs Rs 1250, to Amba Temple it costs Rs 1480, and to Dattatrey Peak it costs Rs 2350. For those who weigh from 70 to 100 kg the cost to Amba Temple is Rs 2850. In 2014 a local doliwala told the author that at Girnar there were approximately 500 doliwalas.

Figure 34. A four-man doli at Girnar, as sketched in the early 19th century (from Postans 1839).

Figure 35. A sign listing prices for the carriage to the top of Mount Girnar, at the doli station at the beginning of the steps up Girnar (photo by Wainer 2009).

According to Junagadh State (1903a, page 156): ‘The steps and the road to the top of Datar Hill, the construction of which was started in 1891 A.D., were completed in 1894 A.D. In the month of November His Excellency Lord Harris, Governor of Bombay, happened to pay a visit to Junagadh, and availing himself of this occasion, His Highness requested His Excellency to formally open the steps and the road. To commemorate the visit this work was called after His Excellency Lord Harris. His Excellency and suite accompanied by His Highness the Nawab Saheb, Vazier Saheb and prominent amirs and principal officers of the administration went up to the top of the hill and performed the inauguration ceremony. In making the request to His Excellency the importance of the Hill and a short history of the Mahomedan sage Jamialshah Pir were dealt on, and the necessity of a road to a place which was held sacred by the Mahomedans, and to which the followers of Islam from distant parts of India repaired in large numbers to pay their homage, was pointed out. His Highness added:–“The pilgrims found great inconvenience in coming up the Hill owing to the want of a proper road, and great steepness from the Shaker Kui to the top. This has now been removed, and I must thank my kinsman Vazier Bahauddinbhai who has contributed very largely to this work. He erected the adjacent Musjid and also the old building, and built these steps as well as the rest-houses half the way at Koyla Vazier, and on the top, at a considerable cost. He has also constructed a reservoir at Koyla Vazier and a step-well at the foot, which are a great boon to thirsty pilgrims. The State has made a bridle-road up to Shaker Kui…”.’

To be continued.

dear sir,

Your information about Mount Girnar is most illuminating and highly valuable.nowhere i have found such detailed description oh history and facts of Girnar put on one page. I salute your research and thank you for this information.

Hi Tarak

Thanks very much for your supportive comment; it really warms my heart. It gives me encouragement to continue uploading similar snippets of information about Girnar and Junagadh.

All the best

John

Sir , it’s really nice information about neminath Bhagvan temple at Urjayanthagiri. Thank you .

gr8 research. what wud b the shortest route to dattatreya temple.

Hi Janvi,

Thanks for your comment.

Most people climb Girnar from Bhavnath Taleti, passing Devkot (3,800 steps), Gaumukhi Ganga Temple (about 4000 steps), Ambaji Temple (step number 4840), and then on to Gorakhnath Peak, Kamandal Kund, and Dattatreya Peak. The only sensible alternative route is from the Taleti, along the old and much less used north-west stairway which passes the turn-off to the Jatashankar Mahadev Temple, up to Seshavan (2,880 steps) and then on and up to meet the regular path at Gaumukh Ganga after another 1200 steps. The two routes cover a similar number of steps.

Cheers

John

Sir, I salute the effort you have made in compiling many Gujarati and Jain history books on this blog. I have just discovered it so I will take some time to read it and hopefully, in the future I can be of some assistance to you.

Hi Ravi. Thanks for your comment. It gives me encouragement to continue to put comments about Junagadh and Girnar on this blog, and also to publish more completed chapters on Amazon Kindle. I have so far only published a handful of chapters, but all of my 33 chapters are fairly complete and ready to go.

Thanks very much for your offer of help. I would appreciate anything whatsoever.

My biggest problem is that I cannot read Gujarati, and therefore cannot summaries what I believe to be some very valuable information about beautiful Girnar and Junagadh. I have scans of lots of Gujarati works just waiting to be read.

I hope to spend a few more weeks in Junagadh later this year.

All the very best.

John

Hii Mr John this information is excellent where the 70 to 80 % of people don’t no that there is second route to climb girnar. Why don’t you even research on deep core areas of girnar where old mysteries are since laying silent even they are from 15 and 16 centuries or more where might time have ruined that places but still today thier might be proof laying thier and lot of thanks for such great full information.

Hi Yagnesh.

Thanks for your positive comments.

You mentioned the possibility of researching other areas of Girnar, and that there might be found evidence of early occupation of these hills. I thoroughly agree with you that Girnar must hold enormous opportunity for exciting discoveries. Researchers have hardly scratched the surface of Girnar’s hidden and forgotten archaeological sites. Consider Intwa, which has had only one brief excavation, and the interesting artifacts that turned up. Or Lakha Medi and it’s fascinating discoveries. In my chapter 25, on Girnar’s ancient Buddhist occupation, I present as much information as I can find on a large number of archaeological sites. In chapter 20, I give info on as many installations as I know of. This includes temples, ashrams, wells, tracks, etc. Chapter 29 covers many of the geographic formations at Girnar, such as hills, rivers, etc. The small section on Girnar’s stairs occurs in chapter 20. All 33 chapters are now readily available at Amazon Kindle Books.

If you know of anything about Girnar, that you think I might have not yet learned about, I would be very happy to read what you say.

All the best

John

Dear John,

we heard in maharashtra that during 12th centure a great saint Dnyaneshwar visit girnar temple ( dattatreya peak ) at that time how was the scenario there ? can you please have information about it. ?

Intresting facts and valuable info

Hi Prasad

Thanks for your question. I have very little information about Dnyaneshwar (Jnanesvar, Jnaneshwar, Jnandev, Dnyanoba, etc) visiting Girnar. I cannot read Sanskrit or Hindi so I have no easy way of learning what the Yogisampradayaviskrti of Dnyaneshwar says about Girnar.

Because Dnyaneshwar visited Girnar, I made a short note in chapter 7 on some notable visitors to Junagadh/Girnar during the historical period:

Jnanesvar

According to Yoga Nath (2012), the great bhakta saint-poet and Nath Siddha Jnanesvar (Jnandev or Dnyanoba) (1275–1296 AD), author of the Yogisampradayaviskrti, within which Girnar figures prominently, had visited Girnar: ‘One time Nivritti Nath, Jnanadev, Sopan and Muktabai, accompanied by Namdev and few other devotes like Narhari Sonar, Chokha-Mela, Savata Mali, went on a pilgrimage to the holy places of India. They have visited Pandharpur, Prabhasa, Prayag, Dwaraka, Girnar, Ayodhya, Mathura, Vrindavan, Hardwar, Varanasi, Kanchi, Ujjain, Tirupathi, Rameswaram, Madurai, Gokaran, and few more places.’

And because Jnaneshwar in his Yogisampradayaviskrti wrote about Girnar, I made a brief note in chapter 19 on some literature accounts of Girnar and Junagadh:

Yogisampradayaviskrti

It was during the reign of Yadav king Ramacandra (1271–1311 AD) that the great bhakta saint-poet and Nath Siddha Jnanesvara (Jnandev or Dnyanoba) (1275–1296 AD) wrote his Yogisampradayaviskrti, within which Girnar figures prominently. Jnandev was the fountainhead of the Varkari movement (Varkari Panth) in the Marathi region (Rigopoulos 1998, White 1996). He was born, and 21 years later attained Samadhi, at Alandi, in the eastern Maharashtra region near Paithana, on the bank of the River Godavari. Among his other Marathi writings are included a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the Jnanesvari (Flood 1996), Svatmanubhava, Haripatha, Amritanubhava, Yogavasietha, Pavana-Vijaya, Pancikarana, etc. (Bhavasar 1997). The Yogisampradayaviskrti has been translated into Hindi by Candranath Yogi, and published in 1924 by Sivnath Sastri, Ahmedabad (Banerji et al 1995). Rigopoulos (1998, page 99) suggested that the attribution of the Yogisampradayaviskrti to Jnandev is dubious.

Just in case you are interested, I have given the references that I sourced for these notes:

Banerji SC, Patanjali and Svatmarama (Swami) (1995) Studies in Origin and Development of Yoga: From Vedic Times, in India and Abroad, with Texts and Translations of Patanjala Yogasutra and Hathayogapradipika. Punthi Pustak, Calcutta.

Bhavasar SN (1997) The Spiritual Contribution of Maharashtra Saints. Chapter 2, In: Sundararajan KR and Mukerji B (Editors) Hindu Spirituality, Volume II, Postclassical and Modern. SCM Press Ltd, London.

http://books.google.com/books?id=UUWIEfAY-mMC

Flood GD (1996) An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

http://books.google.com/books?id=KpIWhKnYmF0C

Rigopoulos A (1998) Dattatreya the Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara. A Study of the Transformative and Inclusive Character of a Multi-Faceted Hindu Deity. Sri Satguru Publications, New Delhi.

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=QTzuXx64d8wC

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ZM-BlvaqAf0C

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=ce0WuAF247wC

https://archive.org/details/Dattatreya.TheImmortalGuruYoginAndAvatara

White DG (1996) The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=6HEnefQRLb4C

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=QDASOTmCxqQC

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=pQuqAAAAQBAJ

https://archive.org/details/AlchemicalBodyWhiteSiddhaTraditionsMRML

https://archive.org/details/WhiteTheAlchemicalBodySiddhaTraditionInMedievalIndia

https://archive.org/details/AlchemicalBodySiddhaTraditionsD.White_201803

Yoga Nath (2012) The great Nath Siddhas: Jnanesvar and Nivritti Nath.

https://sites.google.com/site/nathasiddhas/jnanesvar-and-nivritti-nath

Dear sir,

I want to stay on Girnar peak.

Can you please provide me information of the same and oblige.

Thanks.

Nayan Vora

Rajkot.

Hi Nayan

I might not have much to suggest about staying on top of Girnar, as I have not had much personal experience. One time I stayed at Hanumandhara, where there were a few charpoys in the room next to the temple, but I had to arrange beforehand for the pujari to be there. On another occasion I spent a few nights at Devkot, and that was because my friend Acharya Hemvallabhsuri invited me to stay. He even offered me the opportunity to stay overnight at Seshavan, which is nearby Sitavan near the top of Girnar’s alternative stairway (that bypasses Jatarshankar half-way up).

Now that the ropeway is operating in full swing, I wonder how much things are changing at the Girnar peaks. Due to the Covid-19 restrictions on travel I have not had opportunity to visit Girnar for 12 months, so I do not know the current situation on the ground.

I understand that it has been common in the past for people to spend the evening at places on Girnar such as Kamandal Kund, Patthar Chatti, Sevadas Ashram, Bharatvan (near Hanumandhara), etc. but I cannot give advice as I have not yet done it.

The Girnar ropeway started operation on 24 October and ferried one lakh people in the first 6 weeks, which is an average of about 2,380 per day. Maybe there would have been many more if not for Covid-19. The ropeway starts at 8 am, so to experience early morning, sunrise, etc one would need to climb the stairway by foot or stay overnight somewhere on top.

To have darshan of the fire at the Kamandal Kund dhuni, only available on Monday mornings (before dawn till 9am), it might be better to stay overnight on Sunday – probably best to be there early when pipal (Ficus religiosa) wood is fuelled to the dhuni, to ignite and produce a large flame. The Kamandal Kund website indicates that they have facilities for 30-40 people overnight. Their building extensions have been in progress for quite a while, so there might now be room to accommodate even more people.

Before the ropeway, some people who climbed Girnar could have been too tired to return on the same day – these people may have decided to stay overnight on top and descend the next morning. But nowadays the ropeway takes only a few minutes each way, so people could easily return on the same day. This could help reduce the number of overnighters, but the increase in sheer numbers as a result of the ropeway’s easy access could counterbalance this.

All the best

John

What an enlightening article and such detailed information. I was searching for the information about who built the steps on the Girnar mountain when I came across this wonderful write-up. Thanks a lot 🙏

Thanks Manisha. This note about the Girnar stairway is a tiny extract from Chapter 20 on some important sites at Mount Girnar available online at Amazon Kindle Books – see Kindle Books page on this Blog.

All the best,

John